Julia’s Bat Mitzvah Speeches

Julia wrote two divrei Torah (talks about a Torah topic) for her bat mitzvah:

Saturday, March 14, 2009 Kiddush, Chabad of Silver Spring

I want to say thank you to all of my friends and my family here today to be here at my bat mitzvah celebration Kiddush. I became bat mitzvah on Yom Kippur, but we could not have a Kiddush then because we are not allowed to eat on Yom Kippur. Then we had a break fast. But I wanted to have a Kiddush with all of my friends and family to celebrate.

I want to thank my father and mother for helping me learn Torah. I like the mitzva of honor your father and mother. And I want to thank my sister Barrie for being nice to me and helping to make this day possible. Barrie is a very good sister. I also want to thank all my teachers. My teachers help me learn about everything.

Being a bat mitzvah means that now I have to observe all the mitzvot in the Torah. The Torah is from Hashem. The mitzvot tell us what we are supposed to do and what we are not supposed to do. The Torah is a rulebook for how we live. Life is complicated. It is not easy to know the right thing to do. The Torah tells us what to do. I am happy that Hashem gave us the Torah. That way we know what to do and what not to do.

I like the mitzvot of Shabbat. Shabbat is very important. Shabbat is so important that the days of the week in Hebrew have no name. They only have numbers that count the days towards Shabbat.

Hashem gave us Shabbat as a special gift. The Torah teaches us that one who observes Shabbat is like he keeps the entire Torah. Hashem commanded us to observe Shabbat because He rested on the seventh day after creating the world in six days. Observing Shabbat reminds us that Hashem rested on the seventh day. It reminds us that Hashem created the world. People did not create the world. Hashem did. So we need to listen to Hashem. Hashem created Shabbat for us, not for Himself. He gave us one day to stop all our weekday activities and become kings and queens.

We are commanded to zachor – remember Shabbat, and shamor – to observe Shabbat. Zachor teaches us to remember all the Yes commandments, all of the things that we must do on Shabbat. Shamor teaches us all of the No commandments, the things that we are not supposed to do on Shabbat.

Shabbat is like a queen that comes to our house and puts a special taste in our food. Shabbat is also like a bride and the Jewish people are her groom.

I like our family Shabbat where we have meals together and we learn about the parsha.

We make Shabbat holy by making Kiddush. Daddy makes Kiddush for us. The word Kiddush in Hebrew means holy.

I like to learn about Shabbat, the 39 melachot of Shabbat, what you do and what you don’t do, like we do not pull out hairs on Shabbat. The melachot are kinds of activities. Like plowing, planting, reaping, spinning, sewing, weaving, grinding, cooking, washing, writing, burning or building. All of these kinds of work were used to build the mishkan, the special place that G-d told the Jewish people to build ion the desert after Hashem took them out of Egypt.

On Shabbat, I like to go to shul and follow along with the Torah reading. I also like to daven. When you daven, you daven to Hashem. When we try to daven, all the words go up to Hashem. We can’t see Hashem but He can see us and hear us.

I also like playing Memoir 44 on Shabbat with my daddy and my sister. I also like winning.

Hashem put us in the world so we can do good things. Hashem gave us the Torah so we can daven and do mitzvot, which are good things to do. We can learn to daven and learn Torah so we can let Mashiach come faster. When is Mashiach going to come? I don’t know. But I can help Mashiach come faster by doing more mitzvot. When we do more mitzvot, we make the world a better place. We make the world holy. Then Mashiach can come. If we all do more mitzvot, Mashiach can come very very soon.

Bat Mitzvah Reception Speech, March 15, 2009 Silver Spring Jewish Center

Hello to all my family and friends. I am so happy you are here today with me to celebrate my becoming a bat mitzvah and to celebrate my new book about Penina Moïse. It is my dream to write a book about Penina Moïse. It took two years for me to do my dream, to go to Charleston and write the book. Today I can share my dream with you.

I would like to thank my daddy for driving me to Charleston, South Carolina to learn about Penina Moïse. I would like to thank my mommy for doing the law work on my book, like asking permission to use the pictures. I also want to thank my sister Barrie for being very patient and taking photographs and video in Charleston and of my research in the summer. Barrie helped make this day possible.

I want to thank Mrs. Sohl for giving me the list of people to do for the project, because Penina Moïse was on the list and I picked Penina Moïse . You were supposed to pick a person that you don’t know then write about them. That was the whole point. I did not know about Penina Moïse. I tried to find books about her, but there were no books in the library. I felt pushed inside my heart to go to Charleston, to be the first one to write a book about Penina Moïse. That way, everyone can learn all about her amazing life.

One of the things I admire about Penina Moïse is how she lived her life according to the Torah, even when things were very hard for her. She lived her life according to the teachings in Pirke Avot. Pirke Avot means the ethics of the fathers, special rules for living written down by rabbis about 2000 years ago.

Penina Moïse was a poet and Hebrew school teacher. She was born in 1797 in Charleston, South Carolina. She was the first Jewish person in America to publish a book of poetry. Her poems help people appreciate God and the Torah.

Penina Moïse did not have an easy life. She had to work hard. She was the fifth of nine children. Her father died when she was only 12 and she had to leave school to work to help her family. This is like Chapter 1, mishna 10 in Pirke Avot. Shemaya taught that you should love work. Penina Moïse worked very hard. But she did not give up on her writing.

Penina Moïse published her book in 1833. It was a book of poems called Fancy’s Sketchbook. Penina Moïse loved to learn Torah. Torah study was very important to her. This is like Chapter 2, mishna 19 in Pirke Avot – R’Elazar taught: Put much effort into the study of Torah. Penina Moïse worked very hard at her studying.

From 1838 to 1840, she was a nurse for her mother, who was very sick and could not leave her bed. But Penina still wrote every day. In 1854, she was a nurse in a yellow fever epidemic. This is very serious, because yellow fever makes you throw up blood and die. But Penina Moïse was a good nurse, and she helped many people.

In 1861 Penina Moïse went blind, and stayed blind until 1880 when she died. She memorized everything she read so that when she was blind, she could still learn, write and teach, even though she could not see.

This is like Chapter 3, mishna 10 in Pirke Avot: R’ Dostai bar Yannai taught that “any person who forgets a part of his Torah learning can blame only himself if bad things happen to him.” This teaches us that we must review our Torah lessons and not forget them. Penina Moïse memorized her Torah learning. She kept all her Torah in her head and in her heart. This is also like Chapter 2, mishna 5 in Pirke Avot: Hillel said, Don’t say that you will study Torah when you have free time, because maybe you will never have free time. Penina Moïse did not have free time, but she learned Torah.

Penina Moïse was the superintendent of the Hebrew school at Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim in Charleston. This was only the second Hebrew school in the United States. She wrote poems and made up games to teach the children. She taught hundreds of Jewish children. Later in her life, after the Civil War, Penina Moïse had a school in her house. She taught children even when she was blind and when she was so sick with neuralgia she could not leave her house. This is like Chapter 1 mishna 1 in Pirke Avot – Teach as many students as possible.

Penina Moïse always spoke words of Torah. She spent most of her life teaching children and writing poems and essays about Torah. This is like Chapter 3, Mishna 4 in Pirke Avot: “If three people ate at one table and they did speak words of Torah, it is as if they ate from Hashem’s table.” Now we are having my bat mitzvah reception and we are sitting at the table and speaking words of Torah so we know God is with us here today.

I learned so much from Penina Moïse. Through her poems, her words and her whole life, she taught me to never give up. I did not go to her school. She lived a very long time ago. But I feel like Penina Moïse was my teacher. This is like Chapter 1, mishna 6 in Pirke Avot, aseh l’cha rav, accept for yourself a teacher. This is because a teacher gives you the Torah and teaches you good things to keep you from making mistakes. Penina Moïse teaches us that it is a mistake to give up, that we have to keep trying even when things are hard. I would like to be like Penina Moïse and never give up.

We looked at clues about why Penina Moise was blind. We looked at charts about the brain and nerves. Aunt Carol said that we can’t know for sure why Penina Moise was blind and had headaches. Maybe something was wrong with the nerves in her brain, or she had a tumor, or an aneurysm, which is like a little balloon in a blood vessel. There were no tests or x-rays to see really what happened. So we can’t know why Penina Moise was sick.

We looked at clues about why Penina Moise was blind. We looked at charts about the brain and nerves. Aunt Carol said that we can’t know for sure why Penina Moise was blind and had headaches. Maybe something was wrong with the nerves in her brain, or she had a tumor, or an aneurysm, which is like a little balloon in a blood vessel. There were no tests or x-rays to see really what happened. So we can’t know why Penina Moise was sick. From meeting Susan Lee and seeing her make bobbin lace, I learned things about Penina Moïse. I learned that she was very patient and that she could focus really well for a long time. This is also true of her in her teaching and in her writing poetry, that she kept going even when things were hard. I also learned that maybe making lace made her go blind. Susan Lee explained that many lacemakers went blind from straining their eyes.

From meeting Susan Lee and seeing her make bobbin lace, I learned things about Penina Moïse. I learned that she was very patient and that she could focus really well for a long time. This is also true of her in her teaching and in her writing poetry, that she kept going even when things were hard. I also learned that maybe making lace made her go blind. Susan Lee explained that many lacemakers went blind from straining their eyes.

In the afternoon, we met with Anita Moise Rosenberg, the great grand niece of Penina Moise. She met us at

In the afternoon, we met with Anita Moise Rosenberg, the great grand niece of Penina Moise. She met us at  After showing us the magnificent sanctuary and a collection of portraits and artifacts connected with the Moise family, Anita drove us to the

After showing us the magnificent sanctuary and a collection of portraits and artifacts connected with the Moise family, Anita drove us to the  Julia also interviewed Anita about her family. The Moise family can trace its roots to 1492.

Julia also interviewed Anita about her family. The Moise family can trace its roots to 1492. Julia pointed out that Penina Moise probably wrote several of her alphabetical acrostic poems while living at 5 Coming Street. As she could no longer see, Penina would recall literature, authors, geography and other disciplines in alphabetical order as an aid to memory.

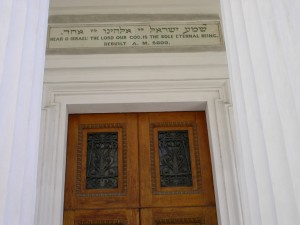

Julia pointed out that Penina Moise probably wrote several of her alphabetical acrostic poems while living at 5 Coming Street. As she could no longer see, Penina would recall literature, authors, geography and other disciplines in alphabetical order as an aid to memory. Wednesday morning, docent Carolee Fox gave us a guided tour of the sanctuary at Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim. The ark is made of mahogany wood from Haiti. Julia remembered that Penina Moise’s parents, Abraham and Sarah Moise, lived in Haiti (then Santo Domingo) before they emigrated to Charleston. Ms. Fox showed us the marks on the sanctuary floor where the original amud stood. Julia was thrilled to see the spot from which Penina Moise would have heard the Torah read. Ms. Fox also explained to us the history of religious freedom guaranteed by the South Carolina Constitution and how groups of all religions cooperate amiably in the city.

Wednesday morning, docent Carolee Fox gave us a guided tour of the sanctuary at Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim. The ark is made of mahogany wood from Haiti. Julia remembered that Penina Moise’s parents, Abraham and Sarah Moise, lived in Haiti (then Santo Domingo) before they emigrated to Charleston. Ms. Fox showed us the marks on the sanctuary floor where the original amud stood. Julia was thrilled to see the spot from which Penina Moise would have heard the Torah read. Ms. Fox also explained to us the history of religious freedom guaranteed by the South Carolina Constitution and how groups of all religions cooperate amiably in the city. Afterward, we toured the covered market, now a gift and craft mall that was formerly a fruit and vegetable market. Julia posits that Penina Moise would have done her grocery shopping for Shabbat at this market. From the market, we continued toward the river to the U.S. Customs House, in continuous use for about 150 years. Back to Pita King (great fries!), then on the road again to Yulee, Florida.

Afterward, we toured the covered market, now a gift and craft mall that was formerly a fruit and vegetable market. Julia posits that Penina Moise would have done her grocery shopping for Shabbat at this market. From the market, we continued toward the river to the U.S. Customs House, in continuous use for about 150 years. Back to Pita King (great fries!), then on the road again to Yulee, Florida. Today, we still managed to do the first third of a walking tour designed by Anita Moise Rosenberg, the great-nice of Penina Moise, showing the houses and businesses connected to the Moise family. We toured the Footlights Theater and saw a mural featuring Isaac Harby, a relative of Penina Moise who wrote plays in the early 1800s.

Today, we still managed to do the first third of a walking tour designed by Anita Moise Rosenberg, the great-nice of Penina Moise, showing the houses and businesses connected to the Moise family. We toured the Footlights Theater and saw a mural featuring Isaac Harby, a relative of Penina Moise who wrote plays in the early 1800s.  Then we walked down Queen Street to Number 46, where Penina’s parents lived with their first six children. In the afternoon, we spent a wonderful hour with Professor Rosengarten at the Addlestone Library, looking at archival materials, newly discovered poems by Penina Moise and discussing Julia’s questions.

Then we walked down Queen Street to Number 46, where Penina’s parents lived with their first six children. In the afternoon, we spent a wonderful hour with Professor Rosengarten at the Addlestone Library, looking at archival materials, newly discovered poems by Penina Moise and discussing Julia’s questions.  Prof. Rosengarten gave Julia many newsletters and magazines featuring Penina Moise to take home to assist in further research.

Prof. Rosengarten gave Julia many newsletters and magazines featuring Penina Moise to take home to assist in further research.